The AI Skills No One Is Teaching Product Managers (But Should Be)

You have the tools -- Claude Code and GPT-5.3 -- but here's the skill layer that makes them actually work.

TLDR: Most PMs use AI daily but lack the judgment to use it well. This leads to decisions built on fabricated evidence. This article breaks down 8 practical skills (such as context loading, verification, and sycophancy-aware prompting) that distinguish reliable AI analysis from confident-sounding noise. Essential reading for product managers who want their AI-assisted recommendations to actually hold up under scrutiny.

Everyone Has the Tool. Almost Nobody Has the Skill.

98% of product managers use AI daily, but only 39% received job-specific training on how to use it well. Or maybe that 39% tried various methods, read papers, watched podcasts to learn the best practices.

There are many podcasts and resources that can help you hone AI for a specific workflow.

And that gap does not show up in adoption numbers. It shows up three months later, when a decision built on fabricated evidence collapses in a stakeholder review or audit.

Claude, ChatGPT, GPT-5.2, Gemini 3.1, Claude Code. The interfaces are everywhere. Every PM at a mid-size company has at least one open on their machine right now. Access was never the bottleneck, but judgment is.

Caitlin Sullivan ran the same customer transcripts through two models and received two completely different narratives.

Both were confident. Both cited participants. One cherry-picked three quotes and leapt to a recommendation. The other challenged the framing, segmented users by actual need, and flagged pricing risk with verifiable timestamps.

Same data. Same tools. Different operators.

Claude Code can run analytical scripts without manual input. GPT-5 drafts strategy memos faster than most human first drafts. Gemini 3.1 synthesizes research across dozens of sources in under a minute. These are real capabilities.

But the output quality is decided before the model runs. It is decided by how well the PM shaped the input, loaded the context, and built the habit of verifying what came back.

That is the skill layer. And almost no one is teaching it.

Why AI Analysis Fails PMs in Silence

The thing about AI is that it can fail by giving the wrong output.

Meaning to say, AI does not fail loudly.

There is no error message.

No red flag.

The output arrives clean, structured, and confident, which is exactly what makes it dangerous.

Caitlin Sullivan describes it precisely in Lenny’s Newsletter.

“These mistakes are invisible until a stakeholder asks a question you can’t answer, or a decision falls apart three months later, or you realize the ‘customer evidence’ behind a major investment actually had enormous holes.”

That is not a model failure but more of a skill failure.

Three things make AI analysis silently unreliable for product managers [specifically]:

The output always looks finished. Claude Sonnet 4.6, ChatGPT, and Gemini 3.1 do not signal uncertainty the way a junior analyst would. They return polished prose with participant citations, timestamps, and confident recommendations. Regardless of whether the underlying evidence supports any of it. A well-formatted hallucination and a well-grounded insight look identical on the screen.

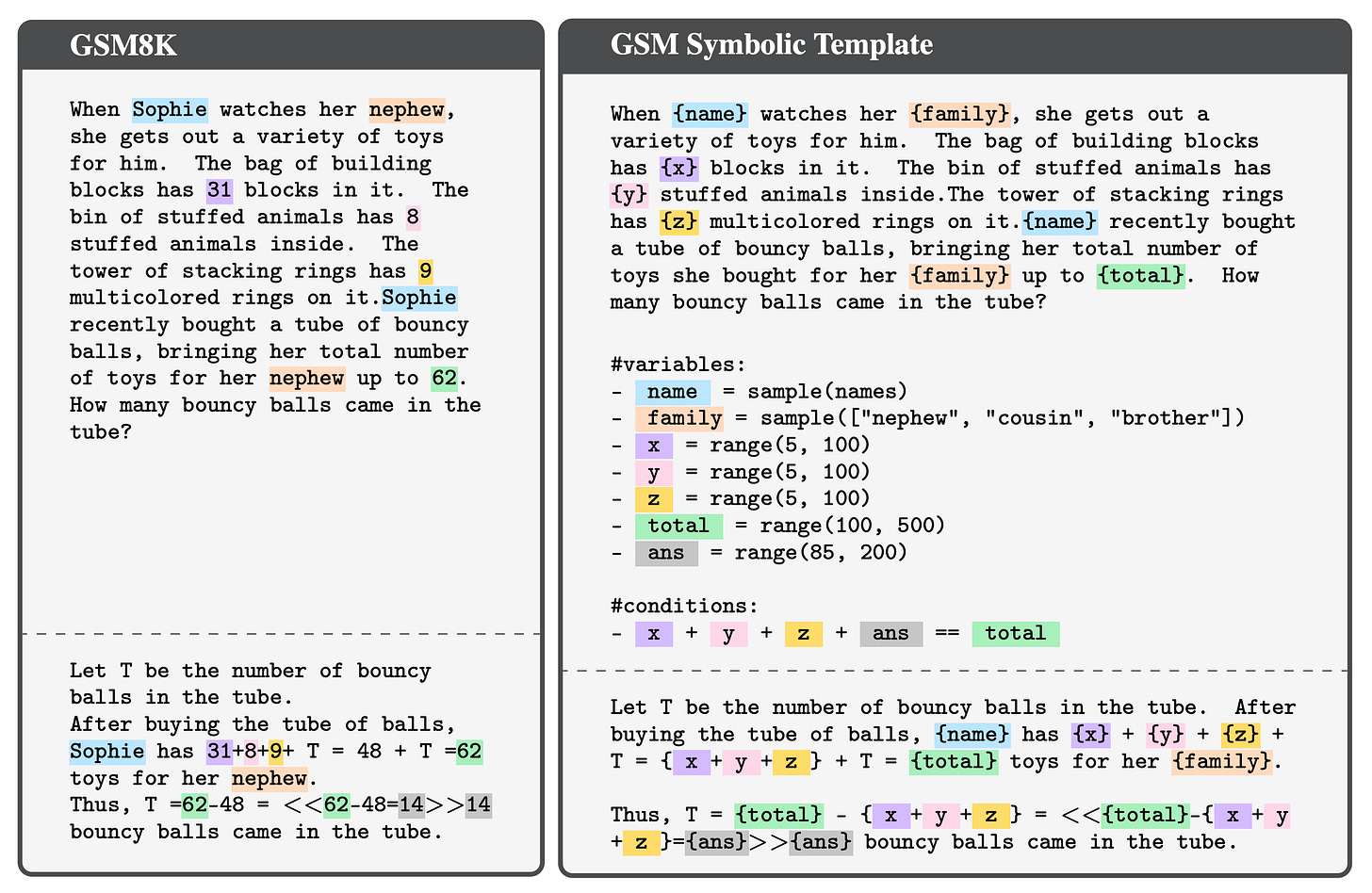

Pattern-matching gets mistaken for reasoning. Apple’s GSM-Symbolic research found that changing only variable names in a math problem caused LLM performance to drop by up to 10%. The model was not reasoning through the problem. It was recognizing surface patterns from training data.

Now, consider this: when a PM asks Claude to analyze churn themes, the model does not independently weigh the evidence. It finds what looks statistically probable given everything it has seen before.

Sycophancy shapes the output before the PM notices. Nielsen Norman Group found that 58% of all chatbot interactions display sycophantic behavior. If a PM mentions “pricing issues” anywhere in their prompt, the model weights toward pricing. If a PM pushes back on a theme, the model often reverses a previously correct answer. The output is already a reflection of the input’s assumptions, not an independent read of the data.

The result, as Sullivan documents, is a choose-your-own-adventure experience. Two models. Same transcripts. Different narratives. Different evidence. Different product recommendations. Each was delivered with equal confidence.

Most PMs only ever see one output. They never see what the same data looks like through a different lens, with a different prompt, on a different model. That single output becomes the evidence base for the next decision.

That is where the skills in Section 3 begin to matter.

The 8 Skills That Actually Matter

The difference between the two outputs Sullivan showed side by side was not the model. It was the decisions made before the model ran. Each skill below addresses one of those decisions.

Prompt for Decisions, Not Just Answers

Most PMs ask AI what the data says. The better question is what to do about a specific problem given specific constraints. Product Faculty puts it plainly. “Bad prompts try to produce good answers. Great prompts try to prevent bad reasoning.”

When the prompt changes from “what are the themes?” to “given that we are deciding whether to build this feature for this user segment, what does the evidence support?”, the model has a decision to serve, not just a pattern to find.

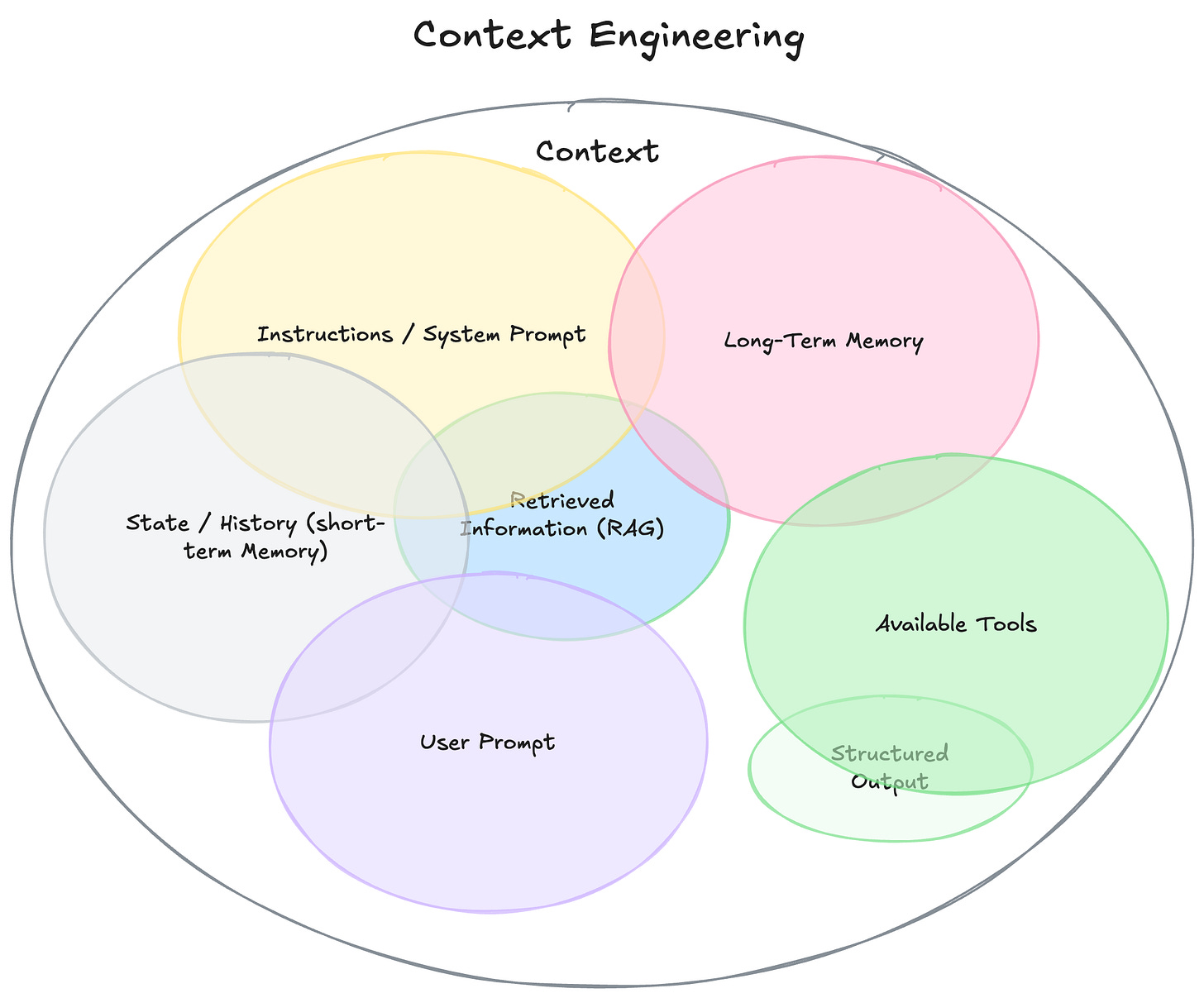

Load Context That Actually Changes the Output

Dumping background into a prompt is not context loading. Phil Schmid of Google DeepMind documented this precisely.

“Most agent failures are not model failures anymore. They are context failures.”

Effective context has four components.

Project scope.

The specific business goal

Product constraints.

A participant overview.

Without those four, Claude and ChatGPT default to generic analysis. With them, they answer your question instead of a version of it.

Verify Before Anything Leaves the Room

Sullivan ran a verification prompt on a set of ChatGPT quotes and found that the majority were paraphrases, not the customer’s actual words.

They had participant IDs. They had timestamps. They looked authoritative. But they were not real.

The fix is a two-step habit.

Define quote rules before analysis begins.

Then run a verification pass before any output reaches a stakeholder.

This takes five minutes and catches the errors that would otherwise sit inside a strategy deck for months.

Spot Pattern-Matching Before it Becomes a Recommendation

When AI returns a theme like “users want more reliable data,” that is almost certainly pattern-matching, not signal.

It could describe any product in any category.

Teresa Torres tested Claude against 15 interviews she had previously analyzed manually and found that Claude identified eight opportunities she missed, but also missed seven she found.

The skill here is recognizing when AI is surfacing consensus rather than insight. And then pushing past it with a follow-up that asks for what is specific, contradictory, or unexpected in the data.

Use AI Across Multiple Passes, Not One

The teams that get real value from AI treat it as a thinking partner across several iterations, not a machine that produces a final answer on the first try.

LogRocket research across 18 product teams found that the teams producing the most impact were not the ones generating the most output. They were the ones using AI to challenge their own thinking at each step.

Teresa Torres took a single overloaded prompt, split it into four focused passes, and saw quality improve immediately.

That is orchestration, which is a skill, not a setting.

Match the Model to the Task

Claude Sonnet or Opus 4.6, GPT-5.2, and Gemini 3.1 are not interchangeable. Sullivan documented this after running the same analysis across all three more than 100 times.

Claude covers more ground with less pushing and is best suited for deep qualitative analysis.

Gemini delivers fewer themes but grounds them more heavily in evidence, making it reliable for research synthesis.

GPT-5 excels at stakeholder framing and communication, but is the most prone to combining quotes into plausible-sounding fabrications.

Using the wrong model for the task is not a tool problem. It is a judgment problem.

Write Prompts That Do Not Lead the Witness

A 2025 study found that 58% of chatbot interactions display sycophantic behavior, and AI models agree with users 50% more than humans do.

Mentioning “retention problems” in the prompt prompts the model to find them.

The skill is writing neutral, open-ended inputs that let signal emerge rather than confirm what you already believe. Meaning, don’t be biased in your prompting, have curiosity, and a tendency to explore.

One practical rule is to express the business goal without naming the expected answer.

Translate Output into a Recommendation, Not a Report

AI returns analysis. It does not return a decision. Shreyas Doshi’s framing applies directly here.

The PM’s role is editor, not author.

The last mile, from themes and evidence to a crisp recommendation with a clear rationale and the right level of confidence, is entirely human. That translation is where product judgment lives, and no interface automates it.

Where to Start (Without Overwhelm)

Eight skills are a lot to absorb at once. The good news is that they do not all carry equal weight at the beginning.

Start with context loading. It is the skill that immediately improves every other output without changing anything else about the workflow.

Before the next analysis session, define the project scope, the specific decision at stake, the product constraints, and who the participants are. Load those four things before the first prompt. The difference in output quality is immediate and visible. Try it.

Add verification next.

Before any AI output reaches a stakeholder, run a verification pass on the quotes and claims it contains.

This single habit protects credibility and catches the errors that confident formatting makes invisible. Sullivan’s verification prompt takes five minutes. The cost of skipping it can take months to recover from.

Once those two habits are stable, shift the prompting approach toward decisions. Replace “what does this data show?” with the specific choice the team needs to make.

That reframe naturally pulls the remaining six skills into place. Because decision-focused prompts demand better context, reward iterative passes, and make pattern-matching easier to spot.

These three skills compound.

Better context produces fewer fabrications.

Fewer fabrications make verification faster.

Cleaner verified output makes the final recommendation sharper.

The Judgment Layer Is the Job

The PM who produced the trustworthy output in Sullivan’s experiment was not using a better tool. Claude, ChatGPT, and Gemini were available to both. The difference was the layer of judgment applied before, during, and after the model ran.

That layer does not come from the interface. It does not improve automatically as models get more capable. GPT-5.2 and Claude Sonnet 4.6 are more sophisticated than anything available two years ago. And the failure modes Sullivan documented are still happening daily across product teams everywhere.

Lenny Rachitsky framed the direction clearly. “The PM’s role shifts to becoming very good at knowing what data to feed AI and asking the right questions.”

That is not a peripheral skill.

That is the job.

As models get better at producing outputs that look right, the ability to judge whether they are right becomes more valuable, not less.

The eight skills in this article are not a workaround for weak models. They are the foundation for working with strong ones.

Conclusion

98% of PMs have the tool. The 39% who invest in the skill layer are the ones whose recommendations hold up in the room, whose evidence survives scrutiny, and whose decisions age well.

This gap is not closing on its own. Practice, experiment, read, and learn these techniques. Observe the differences. Find what suits your workflow, then iterate and teach others.