Claude Opus 4.6 vs GPT-5.3 Codex: Which AI Coding Model Should You Use?

A practical comparison for real PRs; when to use Claude for building and Codex for review, refactors, and reliability.

TLDR: This blog compares Claude Opus 4.6 and GPT 5.3 Codex in the only way that holds up in production. It treats them as different roles, not rivals. You will learn when to use Opus for architecture, deep context, and repo-wide refactors, and when to use Codex for terminal-driven iteration, bug fixes, and test writing. It explains the context tradeoff between large prompts and retrieval, the cost reality that changes defaults, and a hybrid workflow that plans with Opus, executes with Codex, then audits with Opus. You will leave with routing rules you can apply immediately.

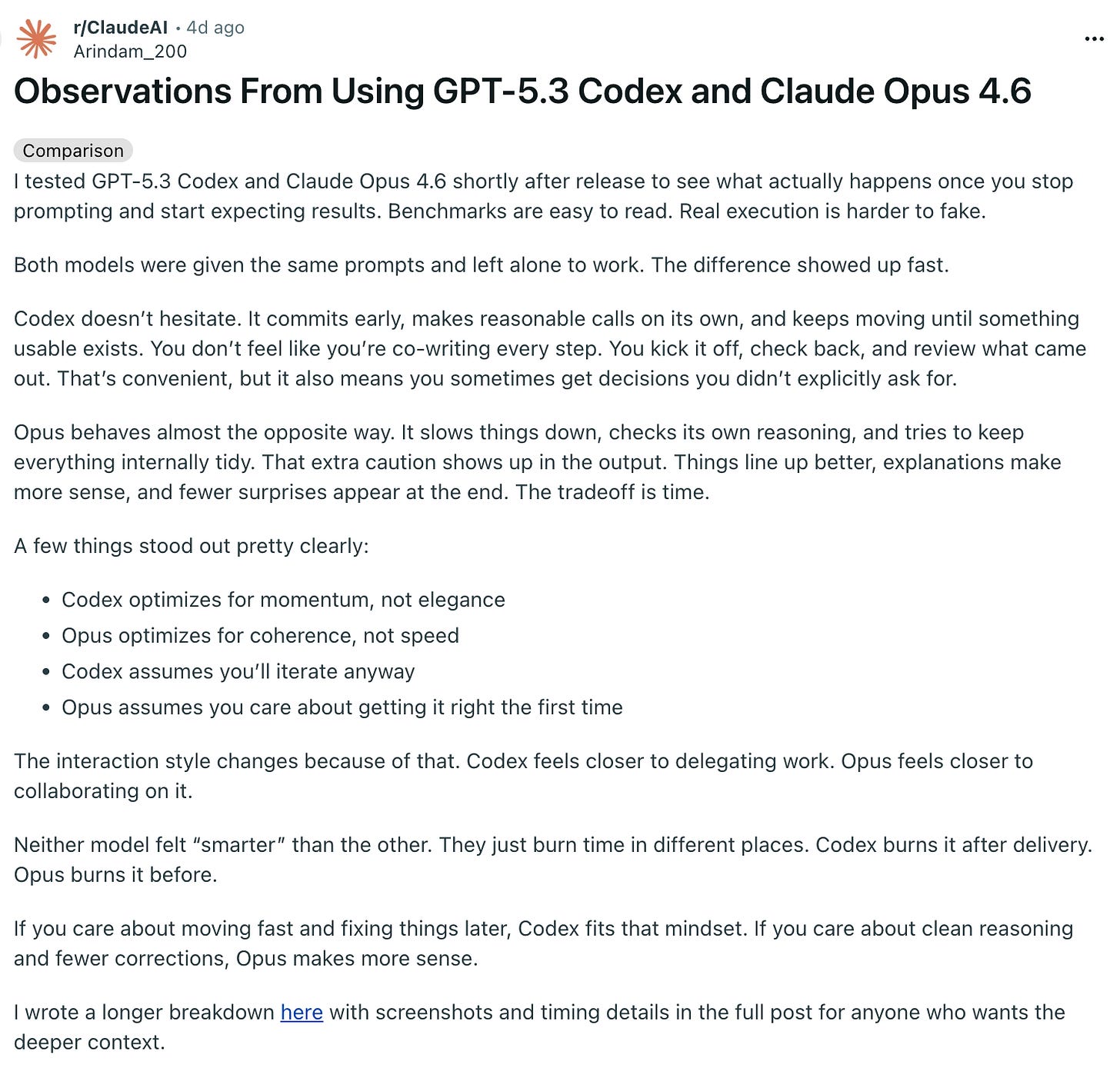

Watching Peter Steinberger talk through Claude Opus 4.6 and GPT 5.3 Codex clarified why this comparison keeps producing disagreement. He describes Codex as the model that reads more by default and stays reliable even when it feels dry, while Opus can run ahead unless you push it into a planning posture.

He also ties modern coding to the command line and explains why terminal fluency matters once agents start running loops for you. That combination pushed me to research roles, not rankings, and to write a guide that routes work by scope and risk.

Claude Opus 4.6 vs GPT-5.3 Codex: Quick Summary

On February 5, 2026, the AI coding landscape changed in a very specific way. Anthropic shipped Claude Opus 4.6, and OpenAI shipped GPT 5.3 Codex on the same day.

The first reaction was confusion. Benchmarks pointed in one direction. Hands-on testing pointed to another. People were looking at the same two models and coming away with different conclusions, which is a signal that the comparison is being framed wrong.

This article uses a simple hiring lens so you can pick the right tool without arguing about winners. Claude Opus 4.6 behaves like a senior architect. It slows down, asks for more context, and spends tokens thinking before it commits to a plan. That deliberation often produces cleaner designs and fewer rewrites when the problem is structural.

GPT 5.3 Codex behaves like a hyperproductive intern. It moves quickly, makes changes early, runs loops, and stays close to the terminal and the feedback cycle. It will break things, notice the break, and patch them in the next pass.

Greg Isenberg captured this as a split between reasoning and momentum. Once you see it that way, the question becomes which role you are hiring for on this task.

What Claude Opus 4.6 Is Best For: Architecture & Reasoning

Claude Opus 4.6 is strongest when the task begins with uncertainty and ends with a coherent design. You see this when the codebase is large, the constraints are fuzzy, and the right answer depends on keeping many moving parts consistent across files.

Anthropic calls this adaptive thinking, a mode in which the model spends time reasoning before it writes.

That deliberation shows up as fewer wrong turns, fewer patch cycles, and fewer hidden contradictions later in the build.

The long context capability matters for the same reason. A large context window is not only about reading more text. It changes how the model constructs its mental representation of the repository.

Opus 4.6 supports 200K tokens, and a 1M token context window is available in beta on the Claude Developer Platform. With enough context, it can track relationships across modules, data flow assumptions, and naming conventions without constantly re-fetching or re-explaining them.

This is why Opus is a good fit for greenfield work that still has real complexity.

Think of an authentication system with roles, session rotation, and audit logging, or a 3D floor plan generator with a geometry pipeline and export formats. The model has to choose an architecture before it chooses syntax.

Alex Carter’s 48-hour deep dive captured the same pattern in a concrete test. He reports that Opus produced a fully functional Kanban board with working drag and drop and clean state management on the first attempt, while Codex failed on the authentication logic in the comparable build.

The tradeoff is cost. The deliberation phase consumes tokens, but it often buys you fewer bugs that only appear after you have shipped.

What GPT-5.3 Codex Is Best For?

If I were to answer that question in three words, it would be “The Speed Demon.”

GPT 5.3 Codex is strongest when the work has a tight feedback loop, and you want the loop to run without supervision.

It behaves more like an operator than a planner. You give it a concrete task, it tries something, it runs the command, it reads the error, then it tries again. That rhythm matters because a large share of day-to-day engineering is not design.

It is repeated compilation, failed tests, missing dependencies, and small fixes that only become obvious after you execute the code.

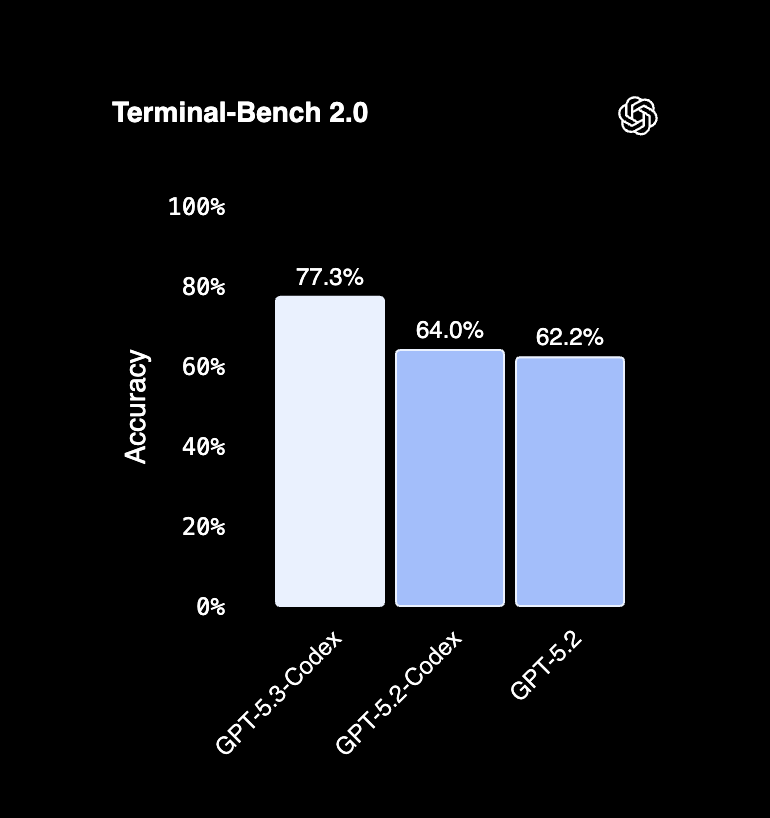

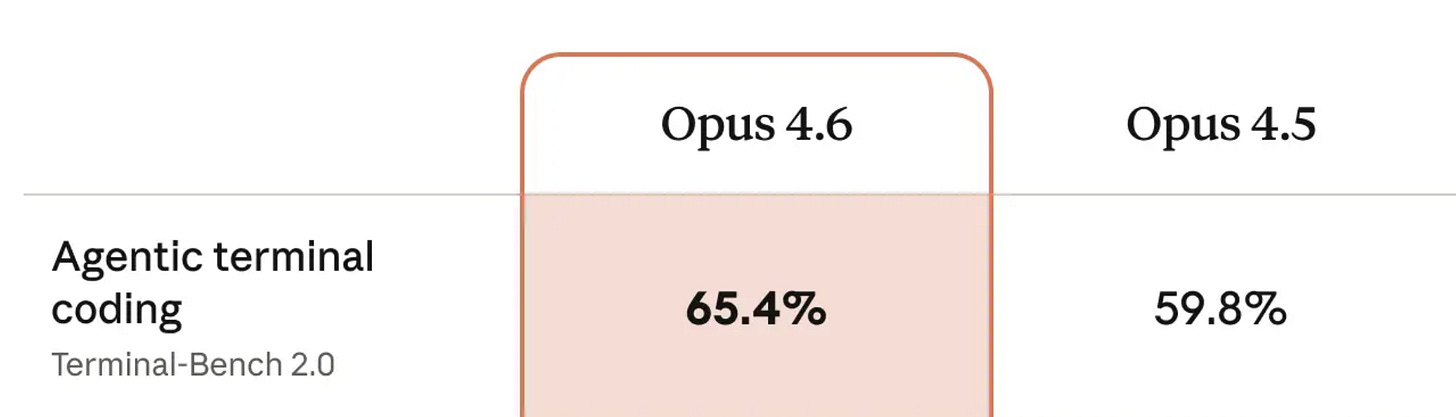

Terminal Bench 2.0 captures this bias toward command line competence. Codex scores 77.3 percent on that evaluation, while Claude Opus 4.6 scores around 65.4 percent in Anthropic’s reported results. Treat that as a sign about where Codex spends its effort. It is built to act inside terminal-shaped work, not only to write a plausible patch.

This creates a distinct momentum mode.

It feels like pair programming with someone who types much faster than you and keeps running the program while you are still reading the diff.

It will sometimes reach for a package or an import that is not in your stack, but the recovery is quick because it immediately hits the build, sees the failure, and corrects the attempt in the next pass.

That makes Codex a strong fit for brownfield work. Bug fixes, unit tests, small feature additions, and cleanup tasks reward speed over elegance. Claire Vo’s experiment is the clearest proof point. She reports shipping 44 pull requests in five days using these models, and her results show Codex behaving like the closer that turns loops into merged code.

The Context Battle: 1M Tokens vs. Repo-RAG

Claude Opus 4.6 and GPT 5.3 Codex can look similar on the surface because both can edit a repository and both can produce working code. The difference is how each model forms knowledge about your codebase.

Opus leans on sheer context capacity.

Opus 4.6 supports very large prompts, with 200K tokens as the standard limit and a 1M token context window available in beta on the Claude Developer Platform.

When you load large slices of the repo, the model can carry a more continuous mental model across modules, conventions, and edge cases. That is valuable during major refactors because the risk is not writing code. The risk is breaking an assumption that lives in a different folder. Migration work like moving an app from React to Svelte is full of those buried assumptions.

Codex often reaches similar outcomes through retrieval.

Instead of holding the whole codebase in the prompt, it pulls the most relevant files and focuses effort there. This is faster and cheaper when the problem is local, but it can miss cross-file invariants because it only sees what it retrieved. The model edits the correct file, yet the change may conflict with a pattern set elsewhere.

Use a simple rule. When a rename or refactor touches dozens of files, use Opus. When a fix lives in a single function within a single file, use Codex.

Pricing & Economics: The $28 vs $0.12 Reality

Economics changes the decision faster than benchmarks.

You can admire Opus 4.6 for its deliberation and still choose not to run it on every small question. The model price is not a rounding error. Anthropic lists Opus 4.6 at 5 dollars per million input tokens and 25 dollars per million output tokens, so long outputs and multi-pass reasoning can add up quickly.

A recent thread on r/SlashClaudeAI made the gap concrete. A user named DutchesForKaioSama described a complex task that came out to 28.70 dollars on Opus, while a similar outcome cost 0.12 dollars on Codex.

Even if you treat those numbers as anecdotal, the ratio is the point. When you pay for deliberation, you pay for tokens and for time spent thinking.

This is why Opus is a poor default for casual chat. Use it like a contractor.

Bring it in when the task has architectural risk, repo-wide consequences, or requirements you cannot afford to get wrong. Keep it out of simple syntax questions, quick formatting, and routine unit test boilerplate.

Codex fits the always on role because iteration is cheap. Let it run the loops. Save Opus for the moments where a careful plan prevents a week of cleanup.

The "Hybrid" Workflow: Manager & Intern

A clean way to use both models is to treat them as two roles in the same engineering loop.

One role produces a careful plan that reduces architectural risk.

The other role turns that plan into diffs and runs the feedback cycle until the work is shippable.

Start with Opus 4.6 for planning.

Give it the requirements, the constraints, and the acceptance criteria. Ask for a short spec, interface definitions, and an implementation plan that is broken into steps you can execute one at a time.

Opus is good at this because it enters a deliberate reasoning phase and maintains more global constraints throughout the design. You are paying for that deliberation, so use it where it changes the shape of the work.

Move to Codex for execution.

Paste the plan into Codex and constrain it to one step. Tell it to implement step one, run tests, fix failures, then stop and report.

Codex is designed for tool-using loops and fast iteration, so it is a strong fit for writing the code, running commands, and grinding through the errors without constant supervision.

Bring Opus back for review. Paste the final diff and ask for a logic and security audit. Focus it on auth flows, input validation, permission checks, and failure states. This is where a slower model can catch mismatched assumptions and corner cases.

Claire Vo describes using different models at different stages of the pull request lifecycle to maximize return on spend, and this workflow turns that idea into a repeatable routine you can adopt immediately.

Decision Matrix & Conclusion

Use this decision matrix when you want a fast answer without rethinking the tradeoffs.

Complex Logic and New App: Use Opus 4.6

Bug Fixing and Terminal Ops: Use Codex 5.3

Refactoring Legacy Code: Use Opus 4.6

Writing Tests: Use Codex 5.3

Note this: You are not choosing a winner. You are choosing a role.

Opus is the call when the work needs a stable design, and one correct pass matters more than speed.

Codex is the call when the work is a loop and the fastest path is to run commands, fix failures, and repeat until green.

The one model strategy is not how teams will work in 2026. The winning setup is a router that assigns work to the right model based on risk, scope, and iteration cost.

Engineers who ship consistently do not pick a side. They pick a roster.