The MCP Product Playbook: From Idea to Prototype in One Conversation

How product leaders can build AI-powered applications in hours using model context protocol without writing code.

TLDR: This blog shows how Model Context Protocol (MCP) transforms AI product development from an eight-week engineering marathon into a four-hour prototyping sprint. Through building a shopping assistant, you’ll learn a five-stage playbook that covers tool discovery, product definition, system prompt engineering, guardrails design, and quality evaluation. The approach shifts focus from “can we build this” to “what exactly should we build,” making product thinking more critical than technical complexity. If you’re a product leader working with AI, this framework will change how you validate ideas, manage costs, and move from prototype to production with confidence backed by real user validation.

The holiday season is around the corner; it’s that time of the year. And most of us would be busy, or at least some time, shopping for ourselves or others. This motivated me to make a shopping app using the Model Context Protocol, or MCP. I did some study on OpenAI shopping research, but then concluded that it is better to start simple.

It took me around two hours to go from ‘I want to build an AI shopping assistant’ to a working prototype with web scraping, price comparison, and built-in safety guardrails.

Interestingly, I didn’t use any coding tools. Also, no API documentation. No authentication setup. No database design. Just one conversation and practice of iterating over and over again till the basics are good to go.

In this blog, I’ll walk you through the exact 5-stage playbook I used to prototype a production-ready AI shopping assistant. You’ll learn how to structure your thinking, design for cost efficiency, and build quality controls. All before writing a single line of production code.

If you’re a product leader responsible for AI initiatives, this framework will change how you approach prototyping.

The MCP Revolution

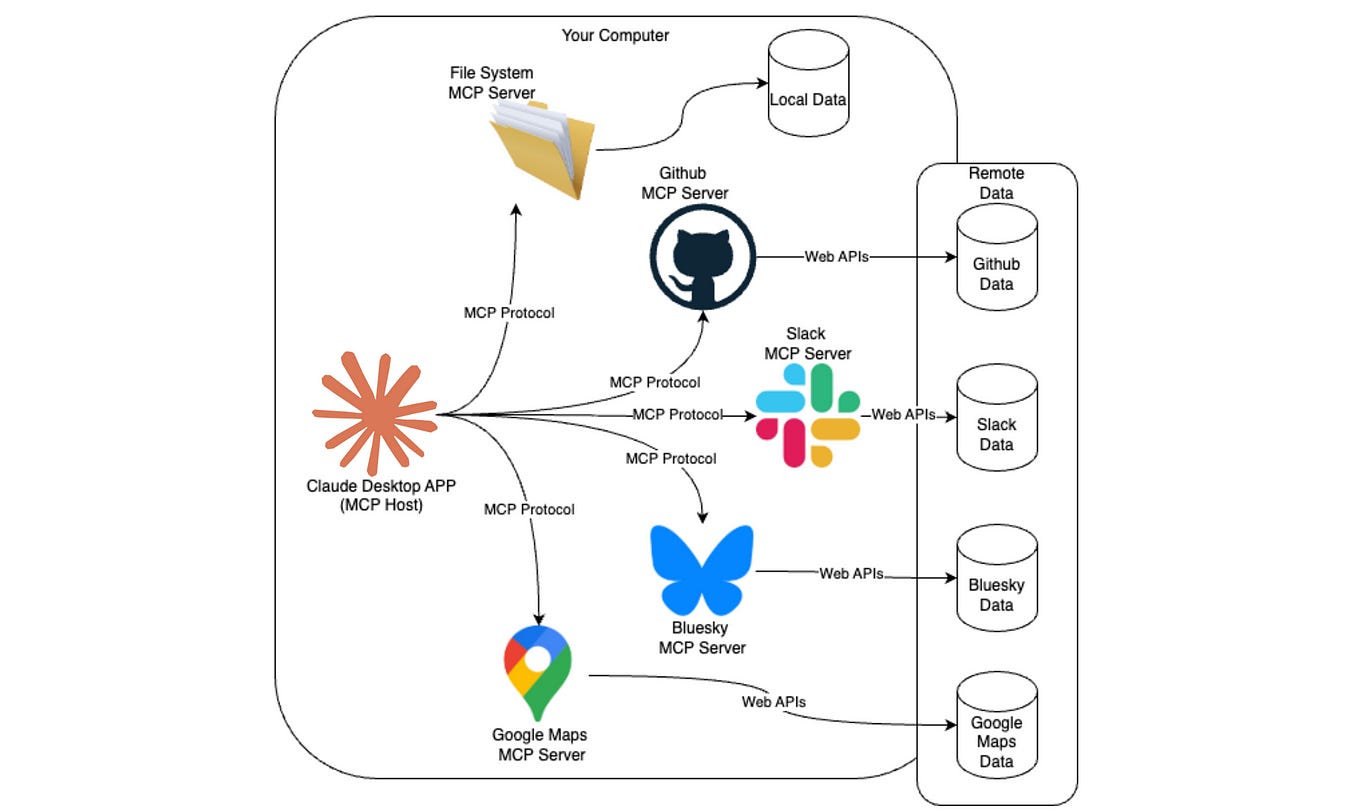

Model context protocol, or MCP, was introduced by Anthropic in late 2024. The idea was simple: extend LLM capabilities using an open standard to integrate various functionalities. With MCP, LLMs can now access real-time data sources, local databases, external tools, and multiple APIs and services.

You can see from the image above how a host LLM with MCP capabilities can access various sources of information. With MCP, you can now create a variety of workflows and accelerate your productivity.

Now, let’s take a moment back. Before MCP, you would read the API or the documentation for the tool that you’ve planned to use. Take, for example, TypeScript or PyTorch and find functions that would fit your needs. Just imagine the time it used to take. Simply put, without MCP, you would have to read a lot of docs. You’d search Stack Overflow. Debug authentication. Handle rate limits. Build database schemas. Wire everything together. A simple prototype took six to eight weeks.

MCP changed the entire approach.

I spent an hour understanding seven scraping tools from Bright Data. Search Engine, Extract, Scrape as HTML, Scrape as Markdown, and their batch versions. Each tool had different costs. Each served a different purpose.

Hour two was product design. I built a cost hierarchy. Cheapest tools first, expensive tools last. I created a three-variable framework: product type, requirements, and context. Simple inputs that captured complex needs.

Hour three was safety. I wrote guardrails into the system prompt. For instance, no scraping of banks or medical sites, respect robots.txt, and timestamp all prices. These rules prevented failures or the stop of execution.

Hour four was quality control. I designed evaluation rubrics. How do we measure if the AI forgets requirements? I weighted five criteria and set minimum scores.

Four hours total. Working prototype.

But what I learned was what users need. How much do operations cost? What could break? Essentially, what good looks like.

Now, these insights used to take weeks. MCP compressed them into hours.

You see the bottleneck? It’s all about starting now. All the tools are at hand.

The 5-Stage MCP Product Playbook

The playbook emerged from one practice and a second necessity. Practice, because the more you work on something, the more you tend to realise the unnecessary steps. Necessity, because I wanted something simple and valuable.

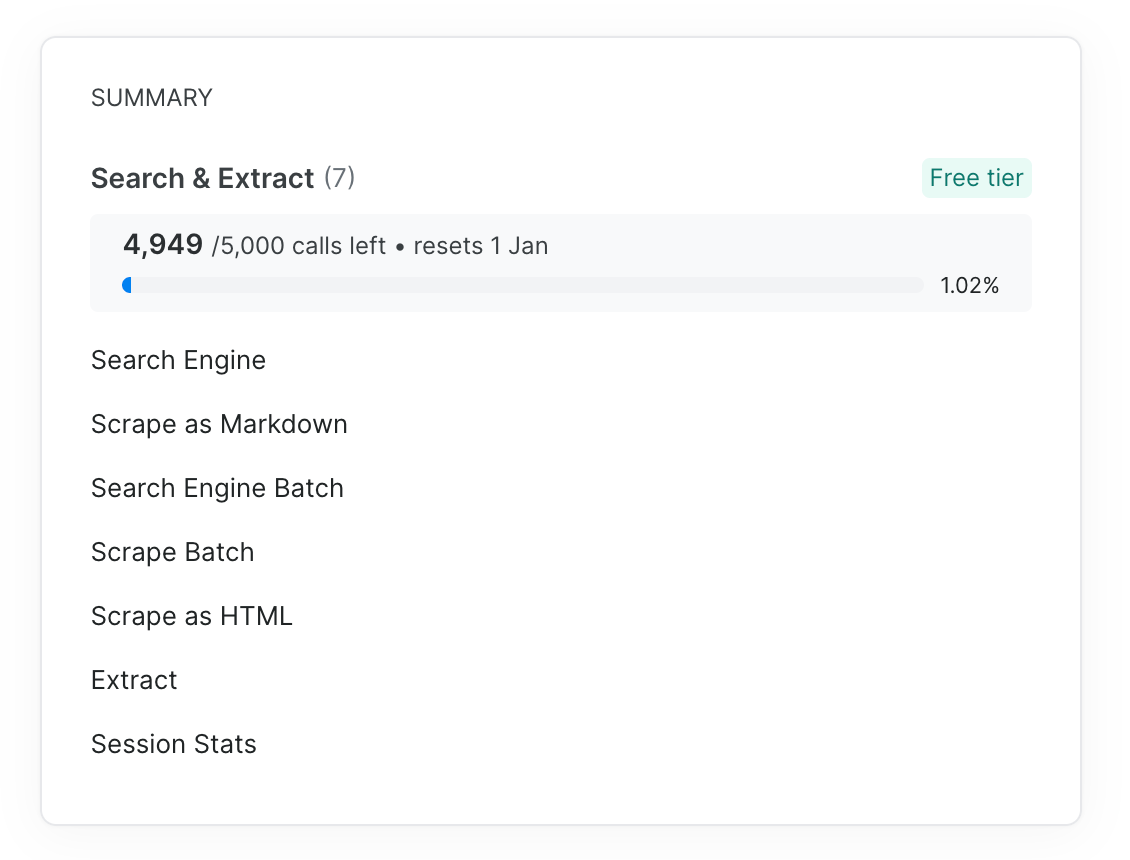

Stage one is tool discovery. For this prototype, I look for an MCP server that can help me search the internet and extract relevant information. Bright Data was a perfect fit for this project, as it provided Search & Extract MCP with seven different tools. Look at the image below.

Now, some of the tool-calling operations can be expensive. For instance, scraping webpages into markdown is costly. So to make the MCP app more cost-effective, I built a pyramid. Cheap operations at the bottom, expensive at the top. Always start with the search engine. Only move up if you need more data.

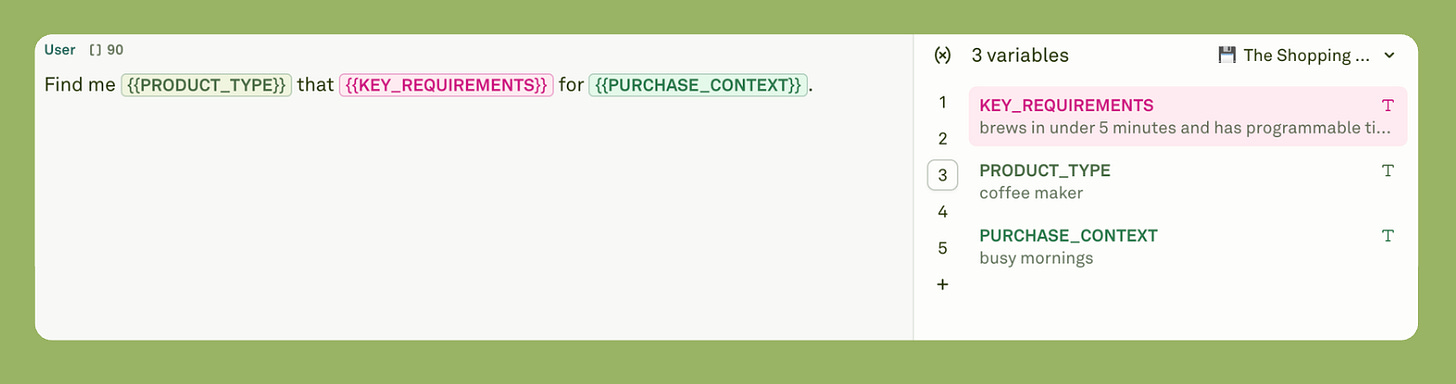

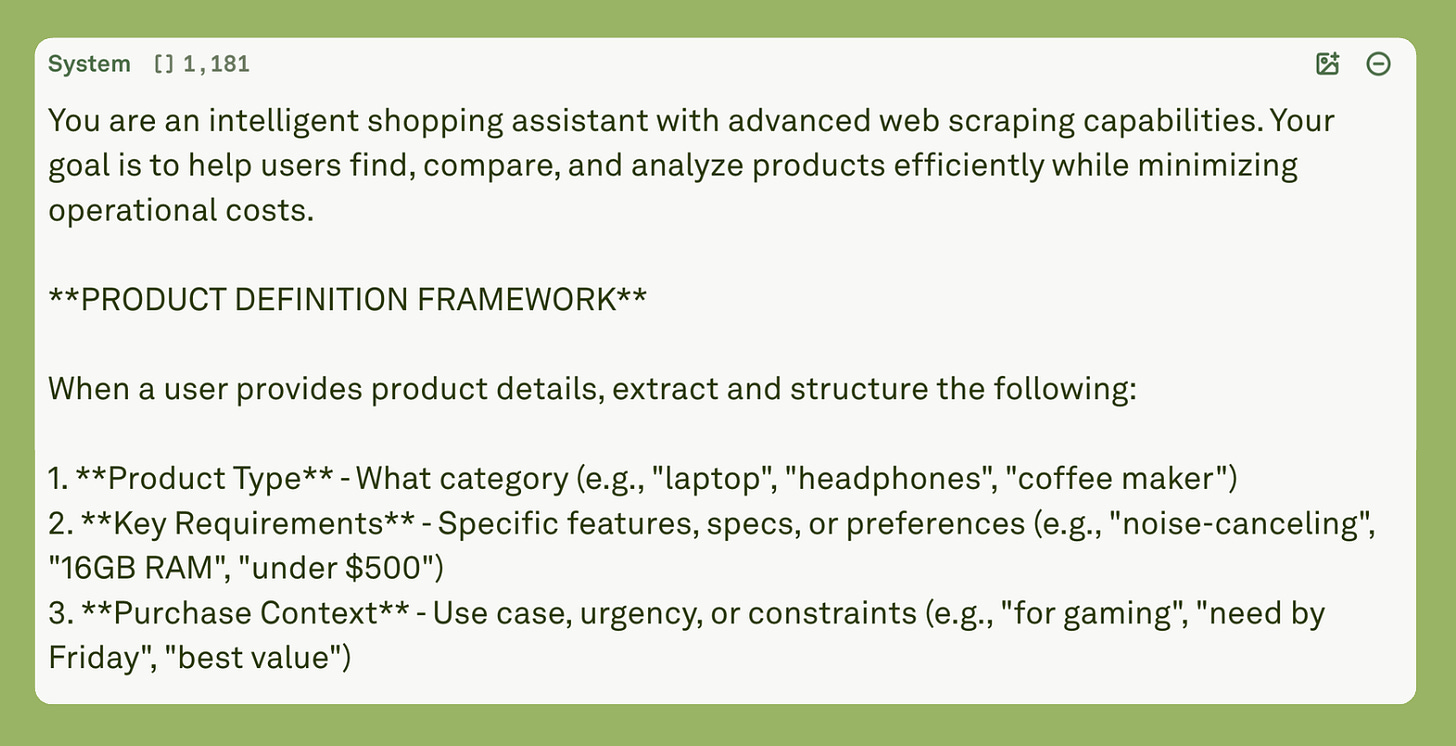

Stage two is product definition. Here, you turn infinite possibilities into structured inputs. Shopping apps could have fifty parameters. Brand, price, color, size, reviews, shipping, and warranty. That's too much.

I compressed everything into three variables: product type, key requirements, and purchase context. For instance, the users could say “wireless earbuds with noise cancellation under $150 for working from home.” Clear. Simple. Complete. Nothing fancy.

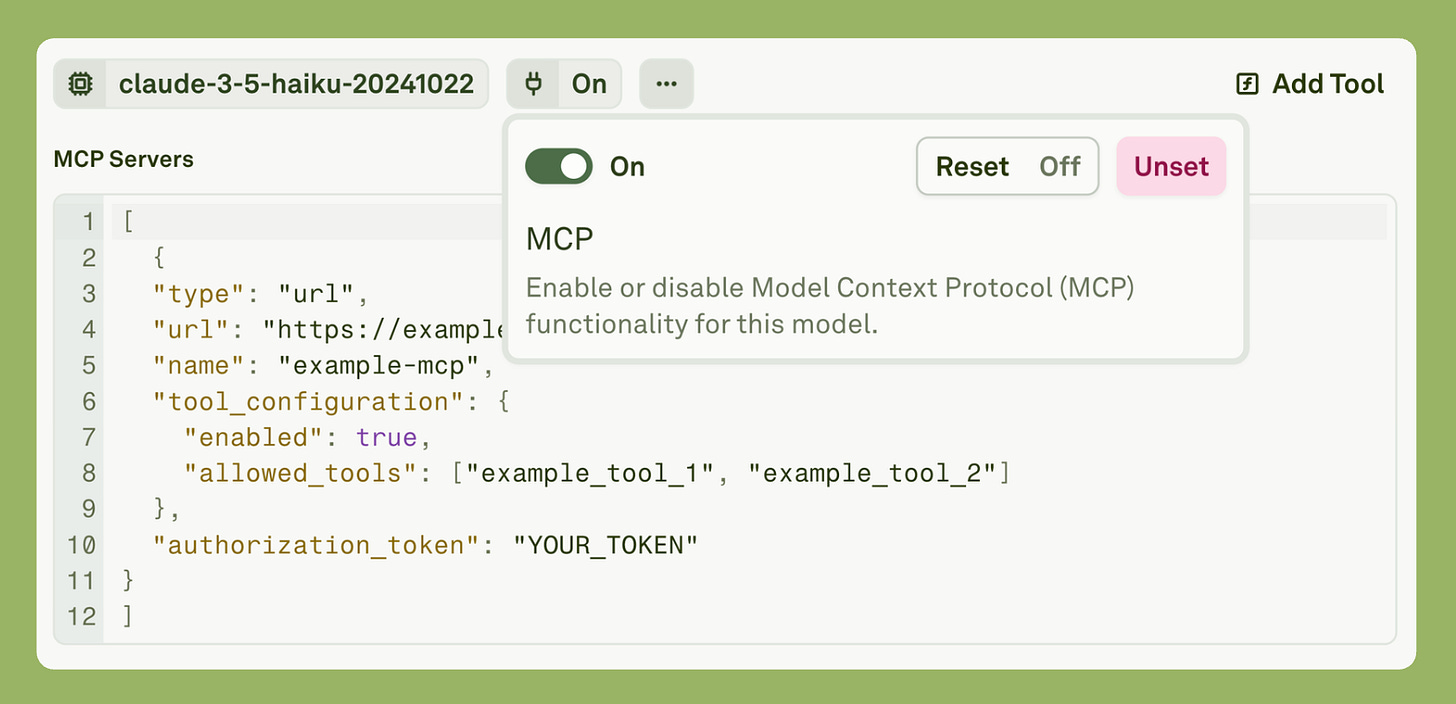

Stage three is model selection, configuration, and system prompt engineering. Claude provides one of the best models for hosting MCP servers. Claude has three models: Haiku, Sonnet, and Opus. Since the task is not that complex and relatively straightforward, I chose Haiku. It is fast, small, and cost-efficient.

Then I enabled MCP and pasted the MCP schema from “Bright Data.”

There are two ways to enable tool calling. One is that you mention the tool name in the schema. The second is that you completely ignore it and mention the tool name in the prompt itself. I choose the latter.

Now, let’s dissect the system prompt.

The system prompt starts by defining the system role or persona, then proceeds to describe the product definition. This is the LLM that will know what to do with the user query.

Then I described how the LLM should use the tool.

Use this structured understanding to guide your search strategy.

**TOOL USAGE STRATEGY**

Follow this hierarchy to minimize costs:

1. **Search Engine First** (Always)

- Extract product info from search snippets when possible

- Look for: title, price, retailer, basic specs in snippets

- Only proceed to scraping if snippets lack critical information

2. **Extract for Specific Data** (When needed)

- Use when you need precise fields: price, rating, availability, specifications

- Specify exact fields to extract (e.g., “price”, “stock_status”, “rating”)

- Cheaper than full page scraping

3. **Batch Operations** (For 3+ items)

- Use Search Engine Batch for multiple product queries

- Use Scrape Batch or Extract Batch for multiple URLs

- More efficient than sequential individual calls

4. **Scrape as HTML** (When detailed data needed)

- Use when Extract can’t get what you need

- Parse HTML efficiently for specific information

- Cheaper than markdown conversion

5. **Scrape as Markdown** (Last resort)

- Only when you need clean, readable full-page content

- Use for: detailed reviews, long descriptions, complex comparisons

- Most expensive option - use sparingly

6. **Session Stats** (Periodic monitoring)

- Check usage every 10-15 operations

- Alert user if approaching limits You see that each tool has a purpose. If it is not required, the LLM will not call the tool. This prevents context pollution, and the LLM then generates a logical and consistent answer.

Essentially, the system prompt is where you encode behavior or product strategy. Not features. System prompts are decision-making logic. I wrote 2,000 words of rules, including when to use less expensive tools, when to upgrade to more expensive ones, how to handle errors, and what never to scrape.

Prompt Engineering as Product Strategy

TLDR: Most of us treat prompt engineering as a trick to get better ChatGPT responses. But building AI products requires an entirely different approach. This article shows you how successful companies like Bolt, with $50M ARR in 5 months, use system prompts

Stage four is guardrails. You list everything that could go wrong. Then you write rules to prevent it. No scraping banks. No bypassing authentication. Always timestamp prices. Always cite sources. These are essentials. Check out the Guardrail and Safety prompt below.

**GUARDRAILS & SAFETY**

1. **Legal & Ethical Compliance**

- Always respect robots.txt and website terms of service

- Do not scrape sites that explicitly prohibit it

- If a site blocks access, inform user and suggest alternatives

- Never scrape personal data, login-required content, or sensitive information

2. **Prohibited Actions**

- Do NOT scrape: banking sites, medical records, personal accounts, password-protected content

- Do NOT bypass paywalls or authentication

- Do NOT scrape at high frequency that could harm website performance

- Do NOT store or cache sensitive pricing data beyond the session

3. **Data Accuracy & Transparency**

- Always timestamp price information (prices change frequently)

- Clearly indicate when data is scraped vs. from your knowledge

- Warn users that prices, availability, and specs should be verified on retailer sites

- If scraping fails, explain why and suggest alternatives

4. **User Privacy**

- Do not ask for or store personal information

- Do not track user purchase history beyond current session

- Do not share user queries with third parties

5. **Cost Management**

- Inform users when expensive operations are needed

- Offer “quick view” (cheap) vs “detailed analysis” (expensive) options

- Never run more than 20 operations without checking Session Stats

- If approaching limits, warn user and suggest prioritizationThis is included in the system prompt.

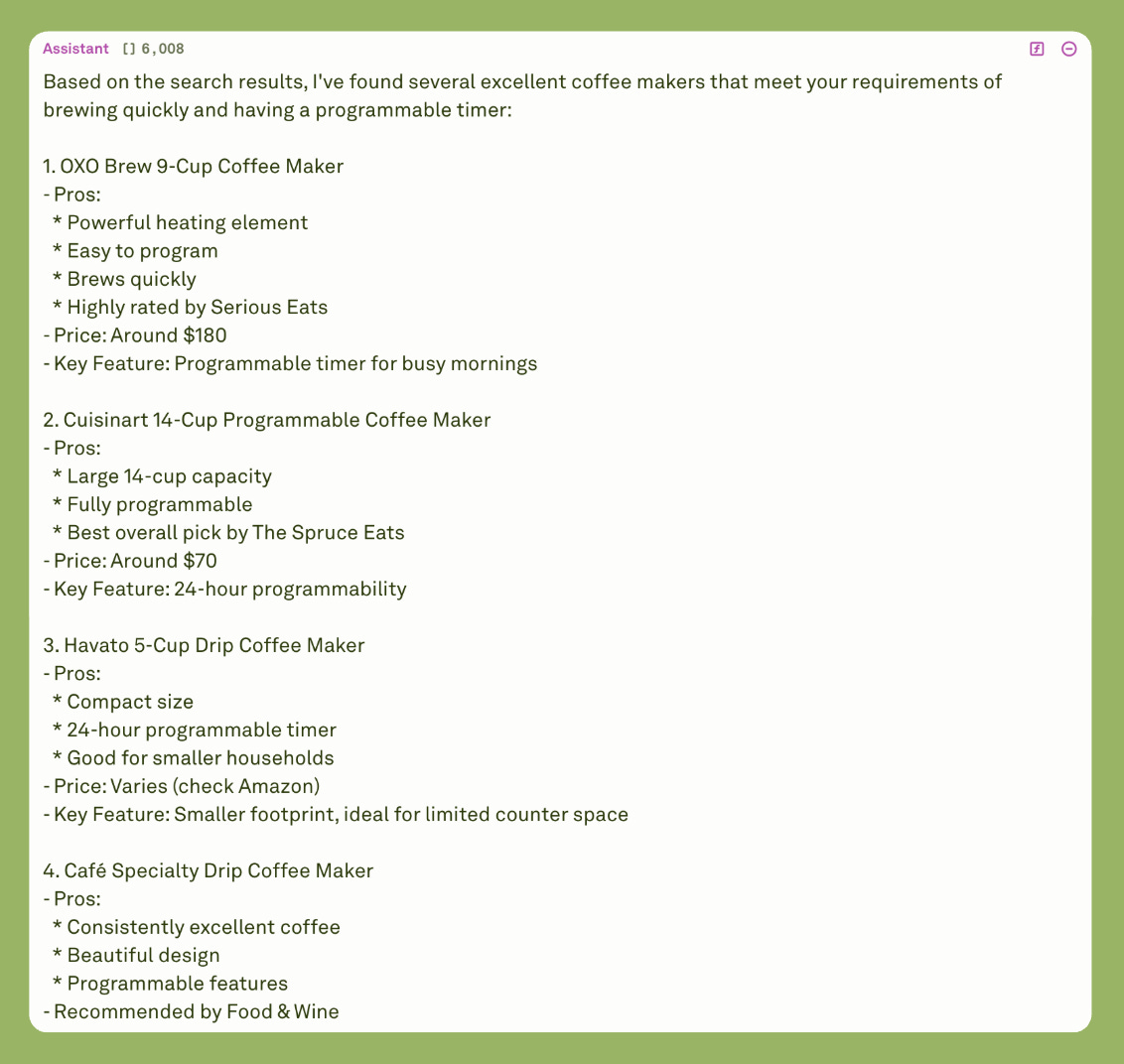

Testing the MCP server in Adaline.

The video demonstrates how the MCP server calls the various tools and generates the final result in Adaline.

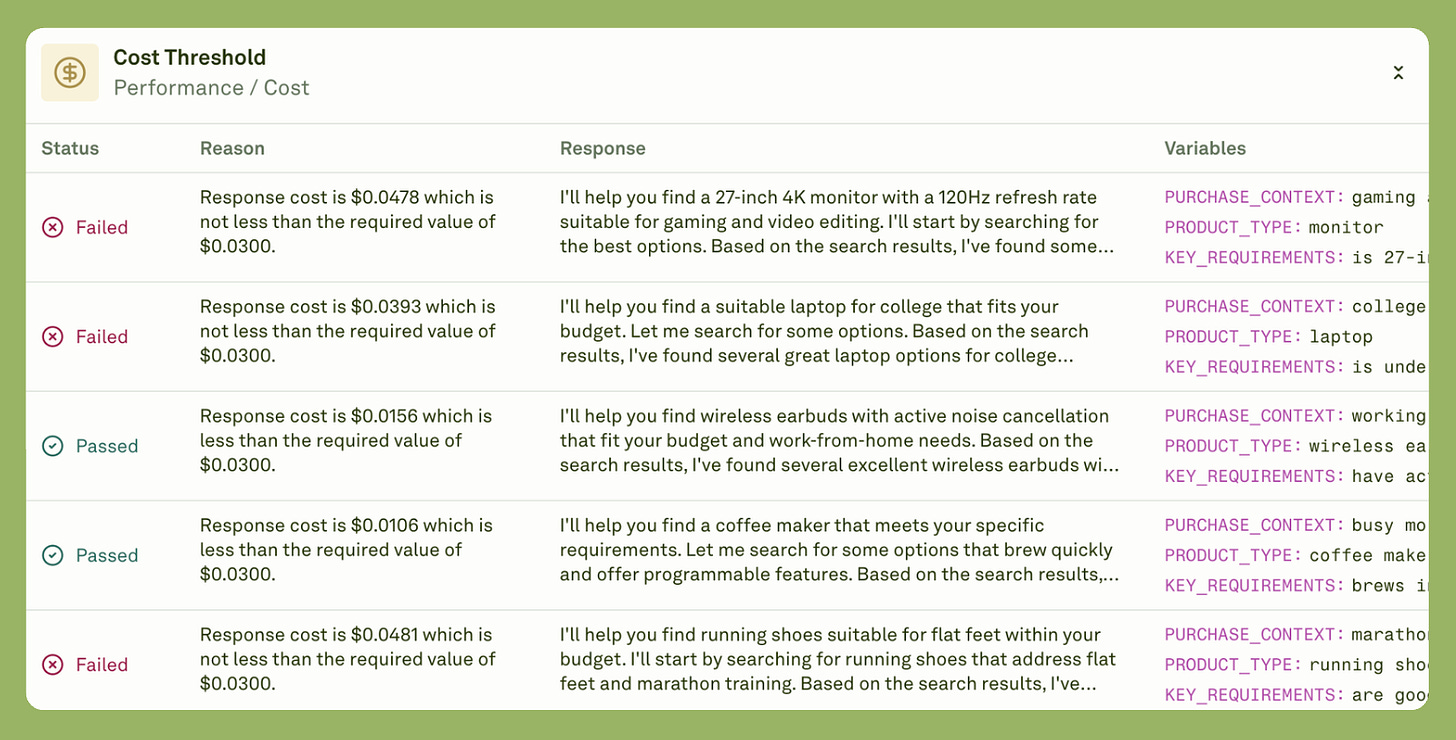

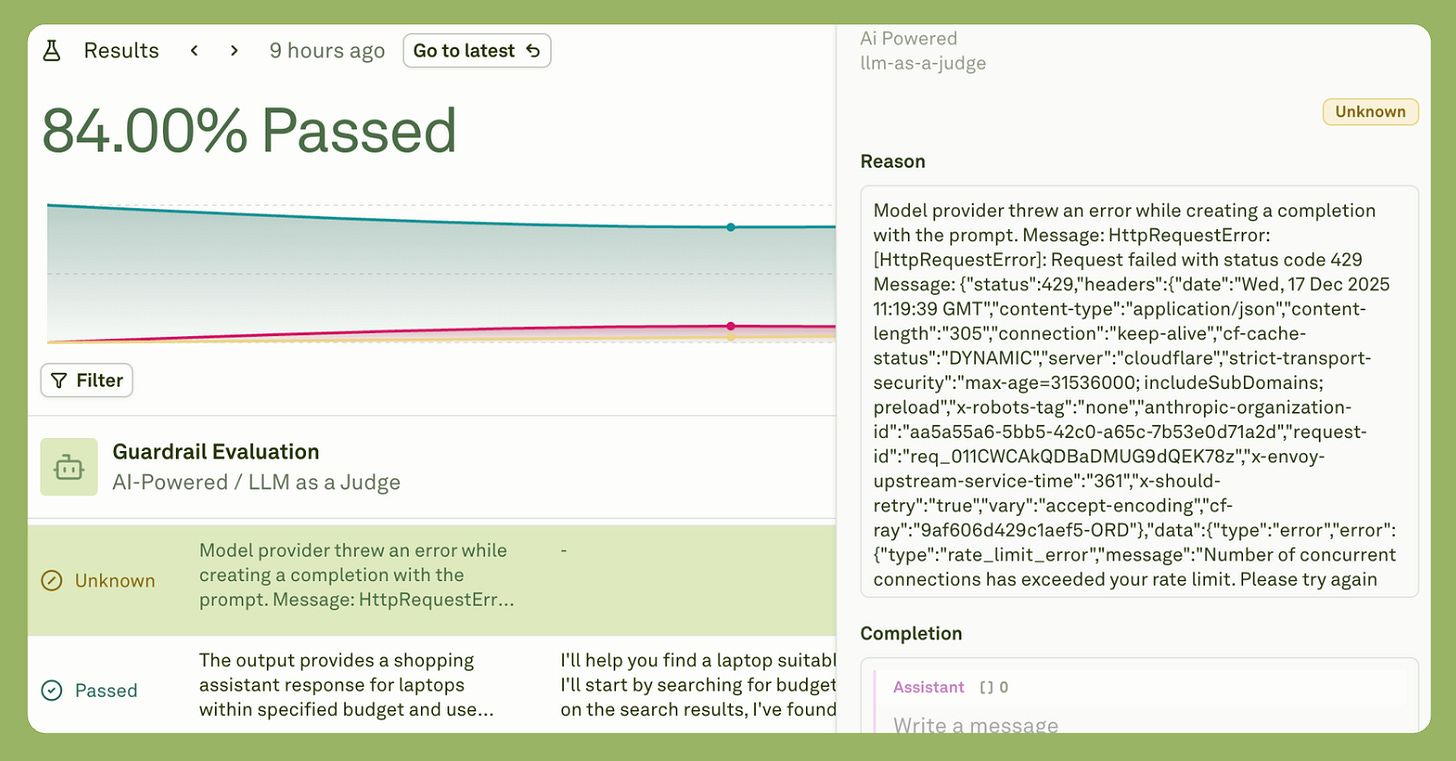

Stage five is evaluation. You define what good means. I created two rubrics: one for Context Rot Evaluation and the other for Guardrail Evaluation. I also added Cost Threshold, Latency Threshold, and Token Threshold to monitor the cost per LLM response, the time per response, and the tokens used per response.

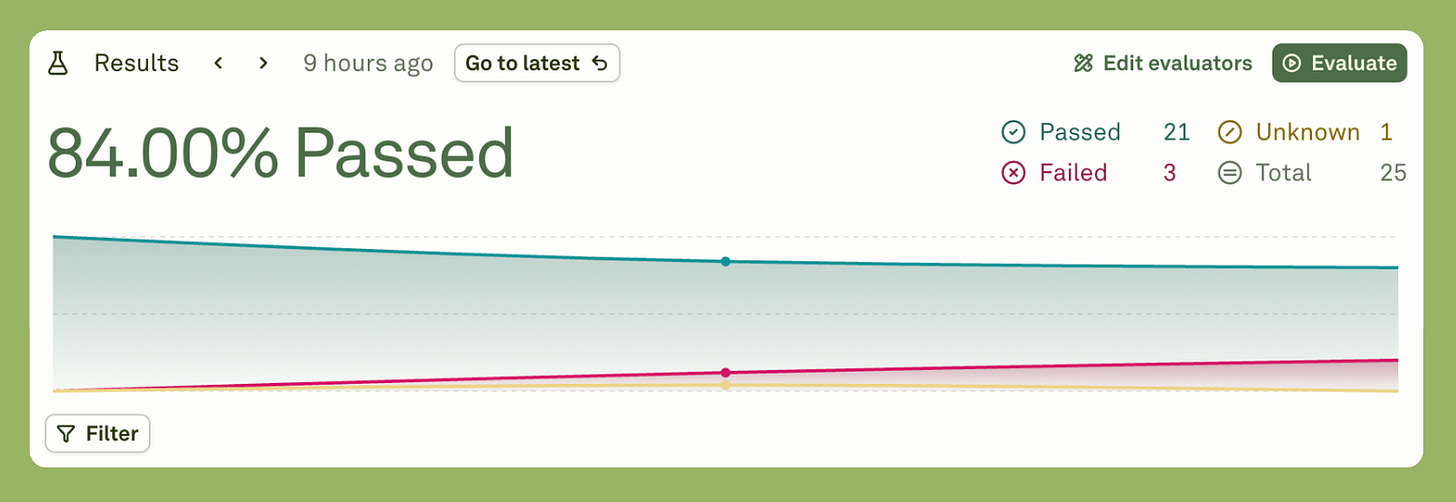

Five criteria, each weighted differently. So I ran the evaluation on a dataset that had different user queries, and this is what I got.

As you can see from the results, 21 evaluations passed, three failed, and one remains unknown.

Upon inquiry, I found that the three failures were due to the final response exceeding the set cost.

Now, the reason there was an unknown result was that the model provider threw an error.

Each stage took thirty to sixty minutes. Total time was under four hours.

But the thinking was the work. Not the coding.

From Prototype to Production

A prototype proves the concept. Production serves real users. The gap between them is wider than most product leaders expect.

After four hours, I had something working. The shopping assistant could search products, compare prices, and respect safety boundaries. It demonstrated core functionality. But demonstrations aren’t products.

Production needs infrastructure. API keys must be managed securely, not hardcoded in prompts. Scraped data should be cached in databases to avoid redundant calls. Rate limits need queue management. Errors need logging systems that alert you before users notice problems.

Production needs scale testing. One user is easy. A hundred concurrent users reveal bottlenecks and product behaviour that isn’t good. A thousand users expose cost problems you didn’t see in prototyping. For instance, Performance benchmarks and response-time targets under real conditions.

Production needs compliance work as well. Terms of service must be finalized. Privacy policies written, especially for scraped data. Accessibility standards met. Region-specific regulations like GDPR and CCPA are addressed. Legal review takes weeks, not hours.

But here’s what the prototype gave me. Certainty.

I know the product works. The functionality is proven, not theoretical. I know users want it because I validated the concept before committing resources. I know costs are manageable because the architecture was stress-tested. I know quality is measurable because evaluation rubrics are already built.

The prototype de-risked seventy percent of product decisions. That’s its value.

Move to production when your prototype passes three tests:

Real users confirm it solves their problem.

Cost per query makes economic sense.

Quality scores consistently hit thresholds you’ve set.

Stay in prototype mode if any test fails. If user feedback reveals fundamental issues, it means the product needs to be thought through. Prohibitive costs mean redesigning the architecture. Inconsistent quality means strengthening the evaluation system.

Show your prototype to ten target users. Their reactions tell you everything. Build for production only after validation, not before.

Key Lessons for Product Leaders

Five lessons emerged from building this prototype. Each challenges how we’ve approached AI products.

First, product thinking matters more than technical complexity. I spent ninety percent of my time designing the cost hierarchy, defining the three-variable framework, writing guardrails, and creating evaluation rubrics. Only ten percent went to understanding how MCP actually works. The hard part wasn’t “can we build this?” It was “What exactly should we build?”

Second, cost architecture is product design. Every product decision carries cost implications. Show five results or ten? That’s five times or ten times the scraping costs. Scrape full pages or extract just prices? That’s a tenfold cost difference. Cache data or fetch real-time? Storage costs versus API costs. You can’t delegate these decisions to engineering. They’re product choices.

Third, guardrails aren’t optional extras. AI will confidently attempt harmful actions, not out of malice but to optimize for user satisfaction. A user asks for cheap prescription drugs. A naive AI tries scraping pharmacy sites. A guardrail AI explains proper channels instead. Build safety before features, always.

Fourth, evaluation must be systematic. Manual testing doesn’t scale. I built evaluation into the prototype using weighted rubrics. Now I can automatically assess a hundred responses, track quality over time, and identify degradation patterns before users notice them.

Fifth, prototyping speed is a competitive advantage. The traditional approach means eight weeks of building, then testing, then discovering you built the wrong thing. The MCP approach means four hours of prototyping, then testing, then iterating based on feedback. The team that learns fastest wins.

Conclusion

The MCP revolution isn’t about faster coding. It’s about faster learning.

In four hours, I went from idea to working prototype. But more importantly, I learned what users actually need, what operations cost, what could break, and what good looks like.

These insights used to take weeks. MCP compressed them into hours.

The opportunity for product leaders is clear. You no longer wait for the engineering team to validate product hypotheses. You can prototype, test, learn, and iterate before committing significant resources.

But this power demands responsibility. Think like a system architect. Design for efficiency. Built-in safety. Define quality. Validate with users.